Dr. Gustav Rau – a life for children and art

Part 1: His path in life seemed to be predetermined

Dr. Gustav Rau (1922-2002) devoted himself to the children in Africa and art. He donated his unique collection to UNICEF.

The son to an industrialist family studied economics to join his father’s profitable company. But at the age of 40 he stepped out of line and began to study tropical diseases and paediatrics next to running the inherited business. Eventually, Dr. Dr. Rau sold his company and devoted his life to two passions – art and children.

He bequeathed UNICEF his unique collection of art to be able to care for the poorest of the poor beyond his death. “I know my material possessions are in good hands,” Rau said. “I entrust them to an organisation that is committed to one cause only, to which I have given my own life: helping destitute children”.

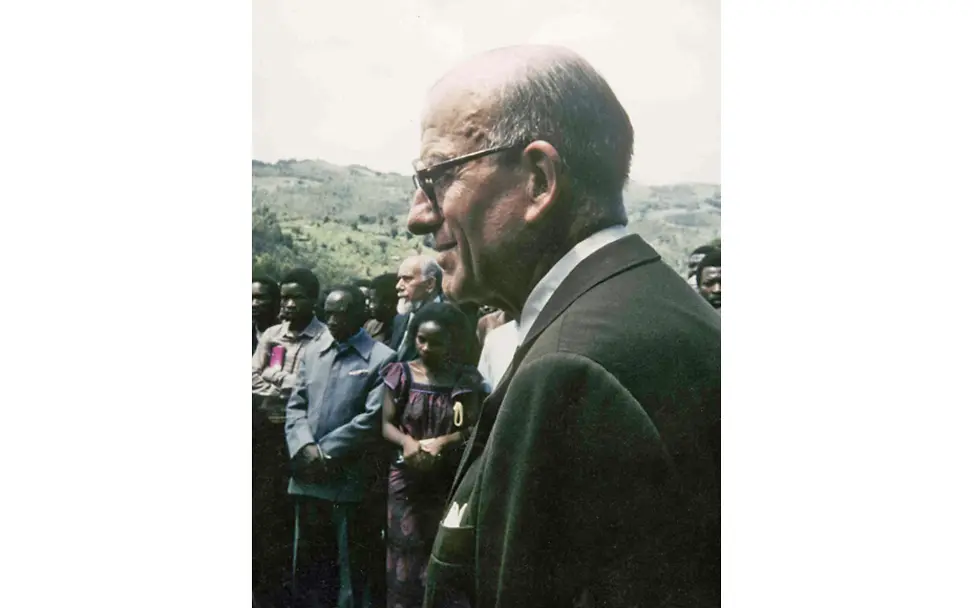

Bild 1 von 3 | Gustav Rau at the opening of the children’s medical unit on November, 23rd in 1983.

© UNICEF

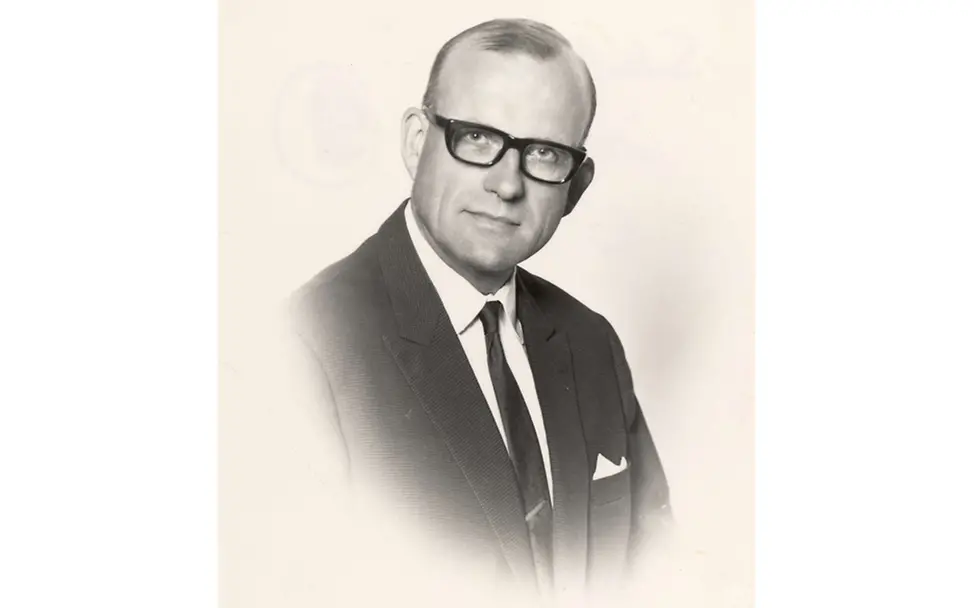

Bild 2 von 3 | Dr. Gustav Rau devoted himself to the children in Africa and art.

© UNICEF

Bild 3 von 3 | Gustav Rau visiting Africa in the early 1970s.

© UNICEF

In the beginning

Initially, it looked like Gustav Paul Ludwig Rau, born on 21 January 1922 in Stuttgart, would follow his father’s footsteps. Gustav Rau senior had turned the Special Tools Factory SWF (“Spezialwerkzeugfabrik”) into a successful manufacturer of parts for motor cars. His mother Elisabeth, born Wieland, daughter of a professor for harp in Antwerp, left him a love for art. Witnesses say that the sole scion described his childhood and youth as a happy time. At first he went to a so called Reform-Realgymnasium but with an eye to his father’s company he graduated from a commercial gymnasium.

In 1942, the student of economics was grudgingly drafted into the Wehrmacht. Like his father, Rau rejected the Nazi regime and the war that Germany had started. He told his friend Werner Kohlheim that he would desert at the first opportunity. His tasks as a soldier were limited to working in an office and as an interpreter. In 1944, he surrendered to the British army in the Netherlands and became a prisoner of war.

After his release in 1947 he continued his studies. For his PhD thesis on “The delineation of the socialist concept of property from the ethical postulates of freedom, justice, and the community” he was awarded the academic title of Dr. rer. pol. Together with his father he ran the car parts company SWF in Bietigheim but his heart wasn’t in it. After his parents had passed away, he started to study medicine in 1963, finishing his studies in 1970 with the academic title of Dr. med. He had thus gone his own way that would lead him to destitute children in the heart of Africa.

As a doctor in Africa

His role model was Albert Schweitzer whom he had visited in Lambarene. In 1972, Gustav Rau sold his parents’ business to an American corporate group. This earned him 443 million Deutschmarks and the liberty to realize his lifetime dream. In 1974 he went to Nigeria as a doctor in the “Sacred Heart Hospital” in Abeokuta. “Almost nothing here can be compared to the situation in Europe. Circulatory diseases seem not to exist here (also my blood pressure has sunk to a subnormal low)“, Rau wrote from Abeokuta on 14 September 1974. “It would seem that Africans have no appendices and dermatosis looks totally different on black-velvet skin than on white skin (we are just 20 white people in the whole of A. with its 100,000 inhabitants and we are called “people without skin”), Mme. Anopheles sees everybody in this hyper endemic region at least once a day (Malaria prophylactics are as popular here as beer is at home), gonorrhoea is an epidemic which is why ectopic pregnancies are very common here, wrong nourishment is a major reason for the ailments of the locals, child mortality is still gigantic.” And he has to admit: “There’s one thing I miss a bit: the thrill of the fine arts.”

Realizing his biggest achievement

Dr. Rau preferred to build a hospital for the poorest of the poor “according to my own plans and with my own hands”. In the Eastern part of then Zaire (today’s Democratic Republic of the Congo) his dream became reality. In January 1977, impressed by reports about the mountain landscape of Kivu, a region in the east of the country, he came to Ciriri in the province of Bukavu, high above Lake Kivu. In 1979, he received permission to build a hospital in Ciriri. Construction began in 1980. The first buildings – 4,000 roofed square meters – were inaugurated by the region’s governor who opened the children’s medical unit in November 1983.

Gustav Rau at the opening of the children’s medical unit on November, 23rd in 1983

Alleviating the plight of the people, in particular the widespread chronic malnutrition became Gustav Rau’s mission. In November 1988 2 doctors, 5 nurses, 5 caregivers, and 18 staff members for general services were working in the hospital. On average, 2,000 adults and children were treated per year and 8,000 were given food and medicine on a daily basis. When civil war erupted in neighbouring Rwanda, the number of people seeking help would at times reach 15,000.

He was helping wherever he could

In the attached centre for malnutrition Rau fought a highly successful battle against hunger – already in 1989, malnutrition in the region was considered eliminated. Giving milk porridge to children proved especially effective. “Within a radius of 2 hours on foot there are virtually no undernourished children who would need to be hospitalized,” a report from November 1988 reads.

The little patients stayed in the hospital between 3 and 4 months to gain 3 to 5 kilograms. Sugar was strictly banned and was replaced by bananas because they are more nutritious and could be grown locally, even at an altitude of 1,900 metres. The children’s diet consisted of maize porridge in the morning, followed by bananas; at ten o’clock milk with bananas; at noon standard porridge made from one third maize, one third beans, and one third vegetables plus bananas; in the evening standard porridge plus bananas. In severe cases, according to their symptoms, children would get additional nutrition such as liquid porridge for rehydration. The recipe is known from an activity report of the hospital: 1 kg ripe mashed bananas, mixed with 1 litre of water, plus 7 g salt, plus 5 g natron bicarbonate. Many patients suffered also from worm diseases (80 percent), malaria (20 percent), anaemia (10 percent), dehydration (4 percent) as well as skin diseases and conjunctivitis.

To bring about a long term improvement in living conditions of the region’s inhabitants, Rau made sure that, next to vaccination campaigns targeting the whole population, 30,000 children could go to school. Schooling fees for needy families were covered up to grade six. Furthermore, the hospital premises boasted a library and a study room. Every Wednesday and Saturday there would be classes for women in raising children and in hygiene. Family planning was also an issue. Rau would as well provide insulin to diabetics. “Nobody can buy it i. pharmacies where they charge ludicrous prices. We give it away for free ... especially to teenage diabetics who can n[ot] live without ... It sells like hotcakes,” Rau writes.

The hospital in Ciriri today

Today, the hospital in Ciriri serves as a reference for the whole southern Kivu region and is responsible for 34 health centres in the environs. Around 215,000 people live in the catchment area of the 130 beds hospital. Every year, 8,500 people are being treated ambulatory. It is run by the archdiocese Bukavu, administered by Caritas International and funded through Gustav Rau’s bequest, by the Foundation of UNICEF Germany and the Foundation Dr. Rau from Zurich.

"He was never boring"

In spite of his wealth, Rau lived reclusively and modestly. Hans Kohlheim whose father was a friend of Rau’s, describes him as a bearlike man, impulsive, laughing heartily, sometimes singing a popular song, and often driven by unrest. For one person or the other he may have been unnerving, also due to some eccentric traits, Kohlheim says. But without these, his lifetime achievement is hard to conceive. He admired Rau for his cosmopolitan outlook and his politeness. “Also children had a say with him. Also for them he was never boring.”

The humanist detested pomp and gaudiness. But there was one luxury he indulged in: collecting art. When his parents took him to museums, his love for painting was awakened, especially for the Dutch and Flemish masters as well as for sculptures.

In 1958, he laid the foundation for his own collection and acquired his first painting at the art gallery Bühler in Stuttgart – “The Cook” by the Dutch painter Gerard Dou. The “collector’s virus” had taken hold of him: from his hospital in Ciriri he travelled to auctions in Paris, London, and New York. Progressively he acquired one of the most extraordinary private collections in the world. In the course of time he bought at least 2,200 objets d’art – many of which he sold if he needed money for his work in Africa or if he was no longer interested in certain fields in his collection.

His collection reads like the “who is who” of art history, from the Middle Ages to the Impressionists of the 20th century: Fra Angelico, Pierre Bonnard, Paul Cézanne, Lucas Cranach, Jean-Honoré Fragonard, El Greco, Max Liebermann, Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, Guido Reni, Auguste Renoir, and many others.

He always had his certain kind of beliefs

“I only bought what I liked,” Dr. Rau once said. With Renoir’s “Woman with rose” it was the melancholic gaze that piqued his interest, a portrait by Dégas attracted him because it was the last self portrait before the artist became blind. Rau took a special interest in the picture of man in all its facets, especially the portrait. In addition, he was fascinated by the vastness of landscapes as well as the microscopically exact close-up view of still lives.

Sometimes, witnesses say, it was pure coincidence that played one or the other piece of art into his hands. While the art dealers could not land in London due to fog, Dr. Rau calmly purchased a Cézanne at an auction. Because of the weather forecast he had travelled by ship to be on the safe side. If possible, he travelled by train and took a picnic basket with him. They even say that he walked on foot from Heathrow airport to auctions at Sotheby’s or Christie’s. Other such walking tours are passed on from other cities.

The frugal Swabian wasn’t always easy on others: on 7 May 1984, for example, he reprimanded his collection representative and later private secretary – on thin air mail paper in dense lines with a type writer and with his typical inclination for abbreviations: “It is a matter of fact that I can never have agreed to buying this office chair – because I would have offered my rolling office chair at the slightest indication of a wish. For myself I would then have used my comfortable, high, white children’s room chair for my ever shorter stays in Mars[eille], as in decades…”